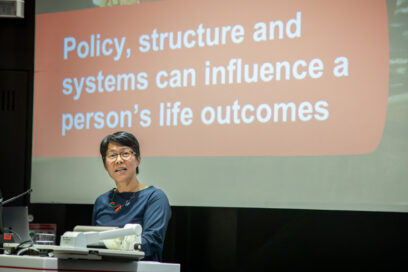

Perhaps the most important thing to understand about homelessness is that it’s not accidental: it’s the predictable outcome of social policy. We have a chronic shortage of affordable housing, we criminalise drug use instead of treating it as a health issue, domestic violence supports are inadequate, mental health services are fragmented and difficult to access, unemployment benefits are set too low, employment opportunities are limited and public housing has been steadily eroded while the cost of living keeps climbing.

We know there’s over 30,000 people experiencing homelessness in Victoria. And yet we have just 423 government funded crisis accommodation beds in Melbourne. (The Crisis in Crisis, 2019 report by Northern Region Homelessness Network)

The impact of this is terrible. People experiencing homelessness in Australia often die 20-30 years earlier than the general population, due to preventable and treatable conditions.

I think what makes homelessness difficult for some of us to understand is that it’s not one thing, it is really just a broad label for a wide range of very different situations.

Some people are surprised to hear that rough sleepers only account for around 6% of homelessness numbers. Most people affected are in crisis accommodation, couch surfing, staying in overcrowded conditions, living in temporary lodgings, refuges, rooming houses, or women and children fleeing from family and domestic violence. Most are invisible.

It’s also worth noting that whatever you say about homelessness, the opposite is also true. It includes people with university degrees and those who never finished primary school. It includes people who have been homeowners and those who have never had a home. It includes people who’ve held well-paid jobs and those who’ve never had paid employment.

But despite these apparent contradictions, it’s important to understand that some groups, those facing chronic disadvantage, poor health, unemployment, disability, and people from First Nations communities, are at greater risk because barriers in the system make finding affordable housing and support a constant struggle.

And yet some people still like to say that homelessness is the fault of the people who are homeless, many of us still frame systemic failure as personal failure. We all know the rhetoric: people make the wrong choices, people lack discipline, people don’t work hard enough.